In Memoriam: Georg Jensen; Designer, Craftsman, Silversmith

by Oscar Benson

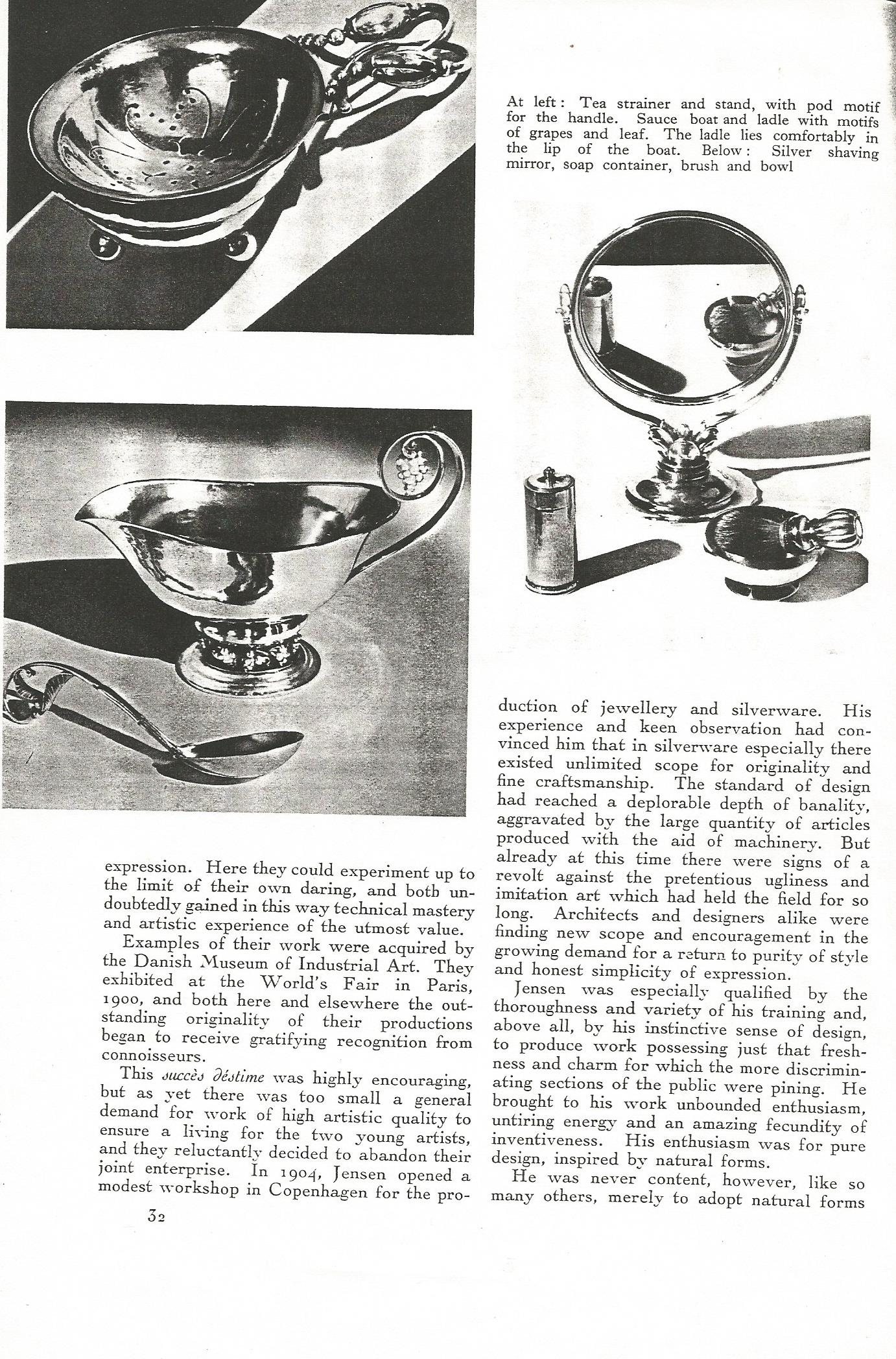

Text is as it directly appears in the article

With the death of Georg Jensen last October, Denmark lost one of its greatest creative craftsmen. It is safe to say that no other silversmith in the present of any other age exercised a more potent and profound influence on contemporary design in his own particular field than this sincere and single-hearted genius.

The depressing period of sterilisation which stultified creative art during the greater part of last century was just coming to an end when Georg Jensen first embarked on his career. Born in the little Danish town of Raadvad in 1866, he was apprenticed as a boy to a jeweller. But his youthful ambition lay in the sphere of sculpture and, while serving his apprenticeship and for some years after, he studied this subject at the local school of art and before long was producing work of unusual promis and strongly individual character. At the age of 26 he won the Dansih Academy's Gold Medal and travelling scholarship which enabled him to pursue his studies and seek wider inspiration in France and Italy.

On his return to Denmark, finding the scope for sculpture to restricted for his restless energies, he ventured into other fields. While earning a living as a designer for domestic pottery he joined forces with a fellow student, Joachin (who later became Art Director of the Aluminia Faience Factory) in producing ceramics of their own design which they fired in a modest oven of their own construction. In this work, carried on in their spare time, their ideas found joyous freedom of expression. Here they could experiment up to the limit of their own daring, and both undoubtedly gained in this way technical mastery and artistic experience of the utmost value.

Examples of their work were acquired by the Danish Museum of Industrial Art. They exhibited at the World's Fair in Paris, 1900, and both here and elsewhere the outstanding originality of their productions began to receive gratifying recognition from connoisseurs.

This succes d'estime was highly encouraging, but as yet there was too small a general demand for work of high artistic quality to ensure a living for the two young artists, and they reluctantly decided to abandon their joint enterprise. In 1904, Jensen opened a modest workshop in Copenhagen for the production of jewellery and silverware. His experience and keen observation had convinced him that in silverware especially there existed unlimited scope for originality and fine craftsmanship. The standard of design had reached a deplorable depth of banality, aggrivated by the large quantity of articles produced with the aid of machinery. But already at this time there were signs of a revolt against the pretentious ugliness and imitation art which had held the field for so long. Architects and designers alike were finding new scope and encouragement in the growing demand for a return to purity of style and honest simplicity of expression.

Jensen was especially qualified by the thoroughness and variety of his training and, above all, by his instinctive sense of design, to produce work possessing just that freshness and charm for which the more discriminating sections of the public were pining. He brought to his work unbounded enthusiasm, untiring energy and an amazing fecundity of inventiveness. His enthusiasm was for pure design, inspired by natural forms.

He was never content, however, like so many others, merely to adopt natural forms as a more or less realistic decoration. He strove rather to master the principles of design and construction which Nature herself employs to achieve her effects. The gracious curve of a leaf, the lovely shapes and grouping of the petals of a flower, the exquisite compactness of a bud: these and countless similar details were the terms of reference from the study of which he gained both inspiration and mastery. His work throughout shows with what remarkable skill he adapted natural forms for the purpose he had in hand, whether the production of a simple bonbonniere, a tea service of a massive wine cooler. One of the most striking characteristics of his genius was the masterly manner in which he disciplined those forms to suit the material in which he worked, using their beauty as a means to express and enhance the beauty inherent in the material itself. From the first his productions were welcomed by connoisseurs for their delightful freshness of conception and soundness of design. Here was a silversmith who, avoiding established forms and stereotypical ideas, had the courage and the skill to create a new style - a style which perfectly expressed the spirit of the age just beginning.

Since then his output has been amazingly prolific and embraces a very wide range of articles. His designs are all distinguished by the same orderly sense of balance and rhythm. Sometimes he relies solely on stark simplicity of form exquisitely proportioned; when at other times, he introduces a certain richness of embellishment it is always restrained, logical and inevitable. He is equally successful in imparting lyrical beauty to a slender graceful tazza or a sense of regal splendor to a massive casket. The magnificent soup terrine shown in the colored plate is undoubtedly one of his finest creations. In this his art seems to have reached the apex of supreme achievement. It is a glorious piece worthy to rank among the noblest examples of silver-craftsmanship ever produced. During the last thirty years the principle museums in Europe and America have been acquiring examples of Georg Jensen's work, and it is safe to say that there are no private collections of note without one or more specimens.

His designs are almost universally used as models for the guidance and inspiration of students, and have exercised an influence, not only on the rising generation but on his contemporaries which cannot be measured. In his workshops are employed more than a hundred silversmiths, some of them apprentices, but most highly skilled experts, and a few who under the aegis of the master have become distinguished in their own right. Among these should be mentioned Harald Nielsen, Albertus and Gundelach-Pederson. For Georg Jensen founded what has since become a very flourishing organisation for producing under his personal supervision exact replicas, entirely wrought by hand in the same manner of the originals, of each of his designs, (and of late years the designs of his leading colleagues). Up to the time of his last illness every piece had to pass his exacting scrutiny before being stamped with his personal mark. In this way the world has been enriched by a far greater number of beautiful examples of silverwork than one man alone could have possibly produced, and so high has the standard of craftsmanship been maintained that replicas and originals rank equally in the estimation of connoisseurs and fetch the same prices.

It is an admirable and probably unique method of handcraft production. Its value was aptly expressed by his fellow-countryman J. C. Nielsen, when he wrote, “Georg Jensen is always the master in the workshop as he is in the world outside, and the institution which bears his name will be able to survive him without betraying him, will be able to go on creating as he has created, will renew its youth in constant rebirth.”